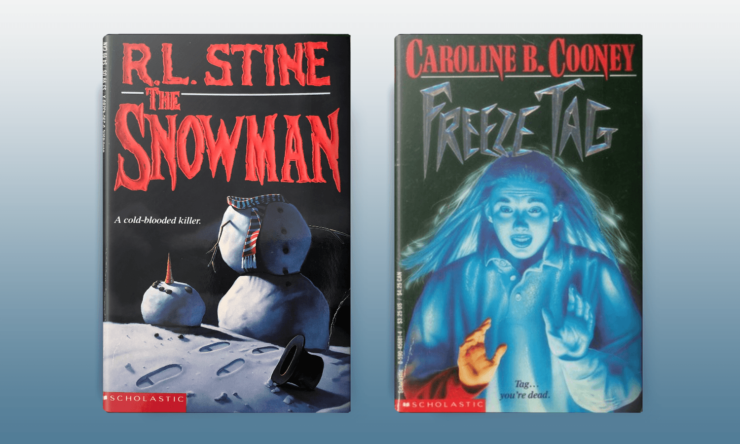

When the snow starts falling and the cold winter chill settles in, the best place to be is warm and toasty inside with a blanket, the fireplace crackling, and a good book. But for our teen horror heroes, sometimes that chill is inescapable, following them into their homes and into their hearts. With R.L. Stine’s The Snowman (1991), nowhere is safe from a predatory stranger, while in Caroline B. Cooney’s Freeze Tag (1992), antagonists and friends both prove dangerous and horrifying.

In Stine’s The Snowman, Heather feels trapped and desperate. Her parents died when she was young, leaving her a trust fund she can’t touch until she’s eighteen–and under the guardianship of her Uncle James and Aunt Belle. Aunt Belle is meek and mild, but Uncle James is a real jerk, going out of his way to insult and humiliate Heather at every opportunity, and in the opening chapters of The Snowman, Heather is actually fantasizing about the different ways she could kill Uncle James. Heather is indulging in these murder fantasies about her uncle while she’s making out with her boyfriend Ben, which is unsettling, to say the least, particularly when she tells Ben she’s thinking about her uncle and he says “How come? Does he kiss better than I do?” (6). From Heather getting a sexual thrill from thinking about murder to Ben eroticizing potential sexual abuse (which there doesn’t seem to be any evidence of in the novel, thank goodness), this is a problematic interaction on a lot of levels. When this opening scene ends with Uncle James’s pronouncement that Heather is “a very disturbed young lady” (11), we can’t help but wonder if he might be onto something.

Heather has a part-time job waitressing at a diner-style restaurant in the mall and to be honest, she is a terrible waitress. She’s frequently late (though she claims to be punctual), is rude to and ignores the customers at her tables, and hangs out chatting with her friends and doing no work at all when they stop in during her shifts. When she heads to work after her confrontation with Uncle James, she meets a mysterious stranger: a handsome guy with white hair, who tells her people call him Snowman because he’s “cold as ice” (22, emphasis original). He seems pretty aware of this ridiculous teen boy posturing as he shrugs and laughs at himself following this exchange, but he still doesn’t tell Heather his real name. He tells her that he just moved to town and goes to her school, though he doesn’t seem to know any of the teacher’s names and she’s never seen him there, and when the time comes to pay the bill, he realizes he forgot his wallet at home and Heather generously offers to pay for his food, saying he can pay her back at school tomorrow (no red flags there, nope). She still doesn’t see him at school after this—and now she’s actively looking—but he keeps randomly popping up at the diner (where he never actually pays for a meal) and lurking in the dark mall parking lot near her car after closing time. It’s not all stalking and free cheeseburgers though—they get together at a park, go to an isolated “secret place” (78) in the woods, and build a snowman, though as they turn to go, Snowman knocks off the snowman’s head in a brief and random fit of violence, then saunters on as if nothing happened.

As Heather breaks through Snowman’s frosty shell, he tells her the sad story of his life: his father was abusive (though he’s dead now), Snowman’s mother works two jobs to try to make ends meet and provide for their family, and he has a sick little brother named Eddie, who desperately needs a kidney operation to save his life. Heather falls for it hook, line, and sinker, and even writes Snowman a check for $2,000 for Eddie’s operation (by then she knows his real name—Bill Jeffries—because you can’t very well make out a check to “Snowman”). He’s manipulative, she’s gullible, and then things reach a whole new level when Snowman murders Uncle James, gleefully telling her that “Your problems are over, Heather. You should be happy” (114). Snowman strangles Uncle James with a scarf, though apparently the paramedics take a look at the body when they arrive at the house and determine that he died from a heart attack, and that’s that, inquiry-wise. The plot thickens when Snowman begins to extort Heather, telling her that if she goes to the police or refuses to give him more money, he’ll tell the authorities that the $2,000 check was payment when she hired him to kill her uncle. (There’s no sick Eddie and no mom who Snowman is struggling to help support. There was actually an abusive dad, but Snowman murdered him).

There seems to be no escape for Heather, as she goes back to feeling just as trapped and desperate as she was in the book’s opening pages, though the snare itself is a bit different. Snowman keeps asking her for money and she keeps giving it to him. He keeps promising to go away, but then he doesn’t. After the big payoff that Snowman swears will really, actually be the last one, he moves into the apartment above Aunt Belle’s garage, and Heather realizes that this nightmare will never end. She reconciles with her ex-boyfriend Ben—who broke up with her after he found out she’d gone out with Snowman behind his back and she told him she’d really rather keep seeing both of them, a proposition with which Ben was definitely not on board—and they break into Snowman’s room to try to get the $2,000 check he’s using to blackmail Heather.

When they find Snowman waiting for them in the dark (it really was a terrible plan), Ben and Heather are both knocked unconscious, Heather is kidnapped, and when she wakes up, she finds herself in their secret clearing, packed inside a snowman, where she will presumably freeze to death. Heather’s not ready to give up just yet and is able to free herself with her dad’s lighter, which she carries in her pocket as a reminder of him. Snowman is similarly tenacious, though, ready and waiting to strangle her with the same scarf he used to kill Uncle James, but she sets him on fire, which is horrifying but effective, as she sardonically thinks to herself “He’s actually lost his cool” (177). Though she’s worried no one will ever find her in this isolated spot, Ben shows up with the police, and when Heather asks how he knew where to find them, he confesses that he followed her and Snowman on their date. Stalking saves the day. (Gross).

While the danger in The Snowman is one of human violence and manipulation, in Cooney’s Freeze Tag, this horror is compounded with a supernatural threat, as the neighborhood kids discover that creepy Lannie Anveille really can freeze them when they play freeze tag. The frozen person is chilled and immobile, frozen in place but entirely aware of what’s going on around them, able to see and hear it all. So Meghan Moore knows when Lannie tells the cute boy next door West Trevor that she will only unfreeze Meghan if West agrees to her demand that “You must always like me best” (18). West promises, Meghan is unfrozen, and they go back to their adolescent summer, never talking about Lannie’s strange and terrifying power, and somehow forgetting its existence altogether as they grow up. Meghan remains close with the Trevor family over the years: Tuesday is her best friend and in high school, Meghan and West fall in love and start dating. It is only when Lannie decides it’s time for West to deliver on his promise that Meghan, Tuesday, and the others remember Lannie’s terrifying power, which they have managed to completely forget in the intervening years.The horrifying memory of freeze tag only comes back to them when Lannie freezes a classmate in the school cafeteria to jog their memories and prove she means business when it comes to claiming West as her own.

Lannie threatens to freeze Meghan, as well as West’s sister Tuesday and brother Brown, if he doesn’t agree. They realize that there’s really no choice, and West breaks up with Meghan and starts going out with Lannie instead. The extortion here is emotional rather than financial, like in The Snowman, but just as effective, with Lannie able to demand complete obedience and compliance from West. And as with Snowman, the truth of Lannie’s family history comes out over the course of this manipulation: when they were all children Lannie’s parents liked their cars (Jaguars) more than they liked their daughter, neglecting her needs and denying her any affection or care. When her parents divorced, Lannie got new step-parents, who both found her unbearably creepy. When her mom died (frozen into a fatal car accident), Lannie’s care passed to her father, and when he mysteriously disappeared (no clues here, but we can guess), her stepmother dropped Lannie back at her stepfather’s door, never to return. As the teens start to remember Lannie’s terrifying powers, they also realize that no one has actually seen Lannie’s stepfather Jason in a long time, and when Meghan asks, Lannie takes her to Jason, who has been frozen behind the wheel of his fancy car (a Corvette rather than a Jaguar) in the garage, where he’ll stay forever.

While Meghan, Tuesday, and Brown offer a united front of resistance, attempting to sneak behind Lannie’s back to find a way to stop her and to save West, they find themselves in an impossible position. Any disobedience or subterfuge is punished with freezing, like when Lannie catches West and Meghan together and Meghan finds herself once again frozen, watching as snow piles up on her open eyes. Meghan reflects on this surreal state, noting that “It was queer the way her thoughts could continue, and yet on some level they, too, were frozen. She did not feel great emotion: there was no terrible grief that her young life had stopped short. There was no terrifying worry about whatever was to come – a new life, a death, or simply the still snowy continuance of this condition. There was simply observation and attention” (87). They are completely powerless to stop Lannie, entirely at her mercy. When West resists, she threatens to destroy those he loves and when he disobeys her, she traumatizes him into submission by making him sit next to Jason’s frozen body for hours.

When West proposes his solution, that “Lannie has to be ended” (133), Meghan is appalled, spiraling further into horror as West begins to brainstorm all of the different ways he could murder Lannie, “with a sort of hot thick eagerness” (134). West, Tuesday, and Brown take an “us versus her” mentality, certain that the nightmare will not end until Lannie has been destroyed, reconciled to the idea that if it takes murder to achieve this freedom, that’s the price they’ll gladly—and even gleefully—pay. After all, Lannie has manipulated, abused, and killed who knows how many people with her terrible power, so really, what’s the harm? While Meghan is horrified by the plan to murder Lannie, she is even more devastated by the change and loss this represents in friends, who have been irrevocably transformed by their hatred and their willingness to hurt another person. As she looks at West, she thinks to herself “There was no going back … This was not West … This was a stranger who would slice off another life as easily as slicing a wedge off a melon” (138), a transformation that breaks her heart. Meghan tells them she can’t be a part of this plan and walks out of the Trevor house, losing both her best friend and the boy she loves. Meghan is devastated and alone, equally horrified by Lannie’s actions, the strength of the Trevors’ hatred, and the lengths to which they are willing to go to stop Lannie.

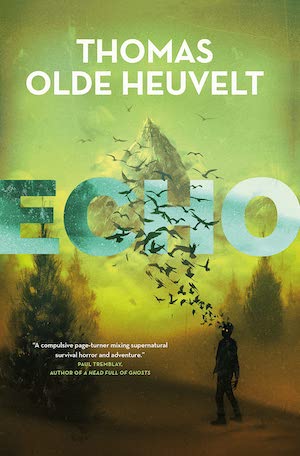

Buy the Book

Echo

When things suddenly and inexplicably go back to normal, with Meghan sharing a meal with the smiling, carefree Trevor family, she comes to the terrifying realization that West, Tuesday, and Brown are happy because they have brought their plan to fruition, that “They were smiling because they knew where Lannie was” (164). West has an old truck down in the woods behind his family’s house, which he has been slowly working on fixing up. He and Meghan often go there to be alone and make out; the truck is also a kind of secret meeting place for the Trevors and Meghan as they work to strategize against Lannie. One thing West hasn’t gotten around to fixing just yet are the inside door handles, which makes it impossible for Lannie to escape. She is trapped, freezing cold, and certain to be dead by morning. When Meghan was unwilling to help “end” Lannie, the Trevor siblings went ahead with their plan without her and with Lannie now contained, their nightmare is close to being over. She didn’t take part in the attack on Lannie but now that it’s done, Meghan has gotten everything she wanted—her boyfriend and her best friend back, everything back the way it was before Lannie’s reign of terror—but she decides she cannot live with herself if she remains silent and complacent, if she lets Lannie die.

Meghan walks out of the Trevor house and down to the truck, releasing a silent Lannie and bringing her home with her. Meghan decides that “This is what it means … to choose the lesser of two evils. Lannie is evil, but it would be more evil to stand aside and silently let her die” (166). Freeze Tag ends in uncertainty, inviting the reader to speculate about what Lannie’s silence might mean, about what’s going to happen next. Meghan ponders this same question, thinking “Perhaps she was too cold to speak … Or perhaps … she had waited all her life to come in where it was warm” (166). We don’t know, Cooney’s not telling, and really, there’s very little in Lannie’s characterization throughout the novel to lend credence to Meghan’s empathetic hope. Maybe Lannie will see Meghan as a friend and be transformed by kindness, but it seems just as likely that as soon as she’s able to do so, she’ll freeze Meghan and her family, then continue her reign of icy terror.

Meghan’s emotional warmth and kindness are a counterpoint to Heather’s literal warmth in the final scene of The Snowman, where she sets her attacker ablaze. In Freeze Tag, Meghan has actively chosen to respond with emotional warmth, supportive rather than combative, grounded in her moral compass and her almost reckless optimism that all people are basically good (even when they’ve shown time and again that they’re really not). While this emotional warmth is a gamble, it is a refreshing response and through the contrasting of Meghan’s choice with the Trevors’, implicitly draws the reader’s attention to the ways in which the teens of the genre are potentially transformed by violence, whether that be what they endure and survive, what they witness, or what they must do to stay alive.

In addition to these two variations on countering coldness with warmth, The Snowman and Freeze Tag also foreground characters who don’t always make the best choices, who may not be objectively “good” people. In The Snowman, Heather fantasizes repeatedly about murdering her Uncle James and while she doesn’t actually kill him herself, she feels nothing but relief when he’s dead. In Freeze Tag, West, Tuesday, and Brown are primary protagonists alongside Meghan throughout the novel, reliable and good friends, though when it comes to Lannie, that goodness is fallible, susceptible to compromise as they work together to plan, execute, and justify a murder. While these characters aren’t uncomplicatedly good, they’re also not irredeemably bad: the reader can see where they’re coming from, can empathize with their feelings, can understand and maybe even agree with the choices they make. While Meghan is the hero of Freeze Tag, we can’t help but wonder: is that the choice I would have made, risking my life to rescue a monster? Or would I sit silently alongside the Trevors, eating ice cream, smiling, and waiting for the nightmare to be over?

Alissa Burger is an associate professor at Culver-Stockton College in Canton, Missouri. She writes about horror, queer representation in literature and popular culture, graphic novels, and Stephen King. She loves yoga, cats, and cheese.